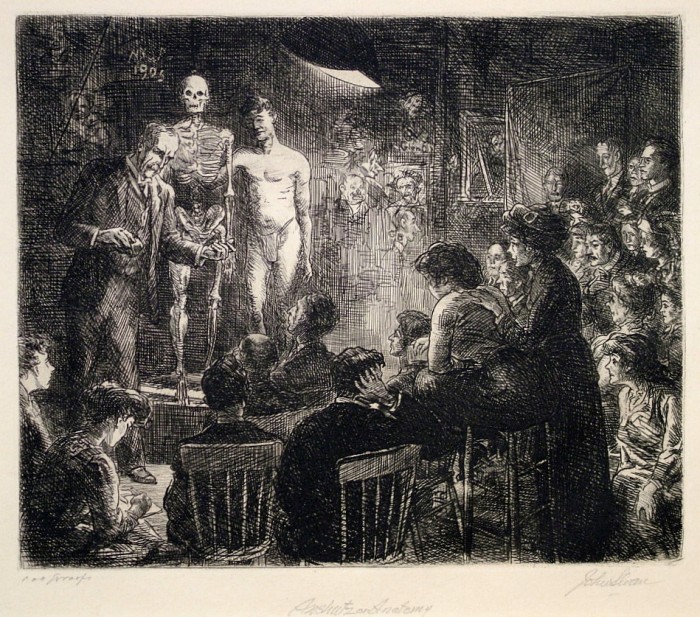

Anshutz on Anatomy

Thursday, September 27th, 2012John Sloan (1871-1951), Anshutz on Anatomy, etching, 1912, signed titled and inscribed “100 proofs” by the artist, and also signed “Ernest Roth imp” by the printer. Reference: Morse 155, eighth state (of 8), from the edition of 80. In very good condition, the full sheet, printed in dark brown ink on a brown/tan wove paper, 7 1/2 x 9, the sheet 11 1/8 x 12 3/4 inches.

A fine impression.

Sloan wrote of this print: “Tom Anshutz, our old teacher at the Pennsylvania Academy, gave anatomical demonstrations of great value to art students. Modelling the muscles in clay, he would then fix them in place on the skeleton. Those present in this etched record of a talk in Henri’s New York class include: Robert and Linda Henri, George Bellows, Walter Pach, Rockwell Kent, John and Dolly Sloan.”

John Sloan can be seen at the upper right edge; George Bellows the second face left of Sloan; Henri is the older man below them and his wife Linda the woman at the lower right. Rockwell Kent noted that “We used to paint all over the walls of the studio, and Sloan shows some of those paintings in his etching. The one bearing the initals GB is probably someone’s caricature of Bellows at that time. The one with “Glen O” under is definitely Glen O. Coleman.”

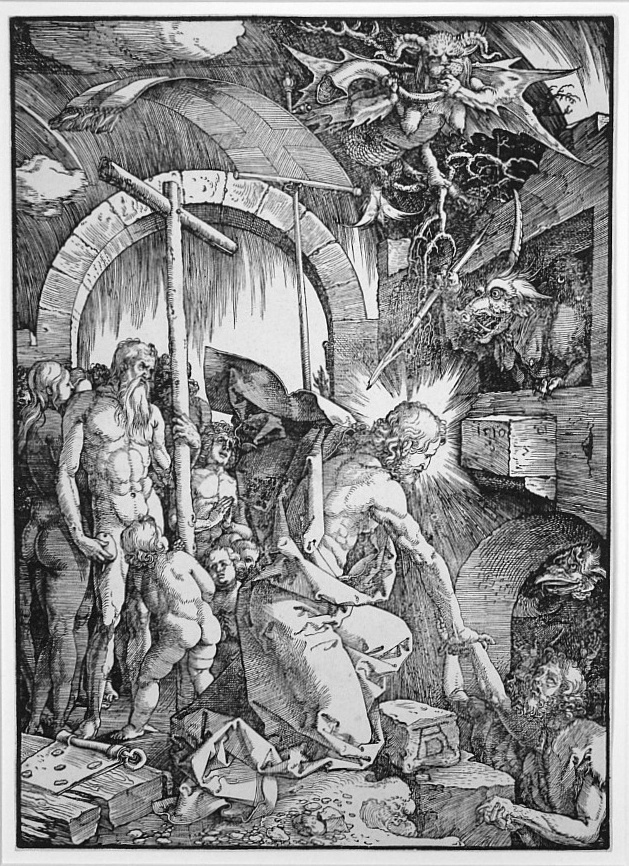

The composition is remindful of Rembrandt’s Petite Tombe, another print depicting people listening (or supposed to be listening) – the composition as well as the subject matter have parallels. And of course this print falls into the great tradition of art illustrating anatomy lessons (again Rembrandt comes to mind, as well as Thomas Eakins, who was a great friend of Anshutz).

This print was exhibited at the famous Armory Show in New York, February, 1913.