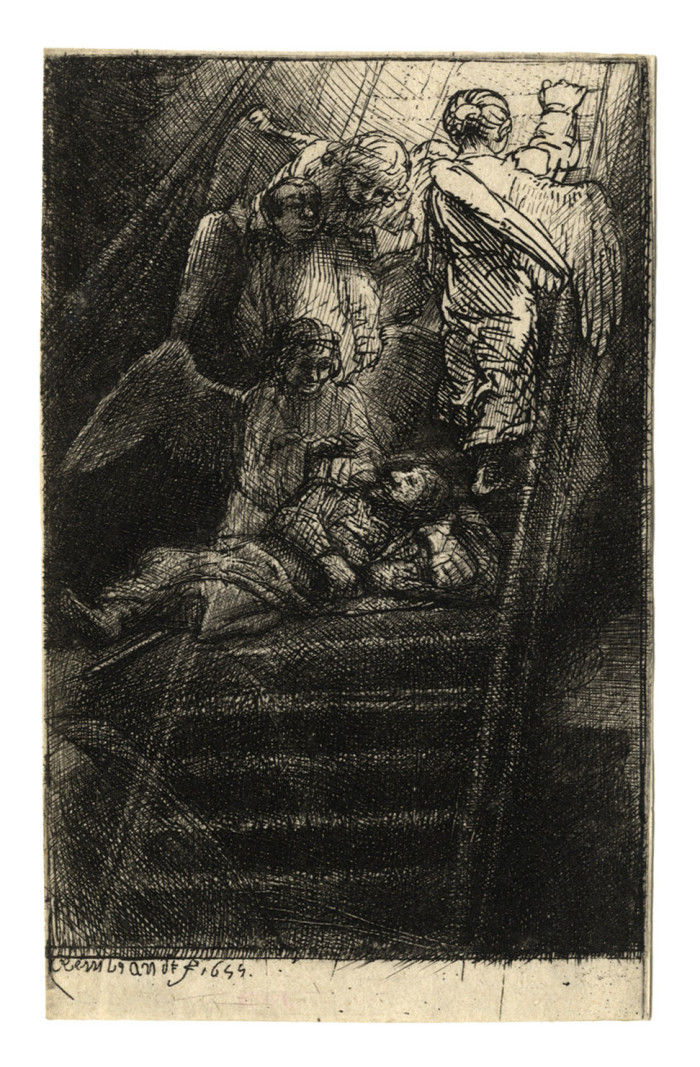

Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn

1606 Leiden – Amsterdam 1669

Jacob’s Ladder, an illustration to Piedra gloriosa 1655etching and engraving with drypoint; 115 x 70 mm (4 1/2 x 2 13/16 inches)

Bartsch 36B, White/Boon third (final) state; Hind 284; The New Hollstein 288b third state (of four)

provenance

Heneage Finch, 5th Earl of Aylesford, London and Packington Hall, Warwickshire (Lugt 58)

John Heywood Hawkings, London and Bignor Park, Sussex (Lugt 3022)

Walter Francis, 5th Duke of Buccleuch, London and Dalkeith, Scotland (Lugt 402)

Kennedy Galleries, New York (their stock no. in pencil on verso a12846)

John William Bender, Kansas City (Lugt 1555b)

A very fine, rich impression with deep burr, with the lower sides of the stepladder burnished in, and the whole dense lower area printed effectively with the utmost care; before the plate was reworked in drypoint.

Jacob’s Dream is one of four etchings that Rembrandt composed on one plate, intended to be cut into four for use by the publisher as illustrations to a book by his friend, the rabbi, scholar, publisher, and diplomat Menasseh ben Israel (1604–1657). (The other images show The Statue of Nebuchadnezzar Overthrown; David and Goliath [B.36C]; and Daniel’s Vision [Bartsch 36A, C, and D respectively].) This work, written in Spanish and titled Piedra gloriosa de la estatua de Nebuchadnesar, was published in Amsterdam in 1655. It is a mystical tract in which a series of episodes from the Book of Daniel are seen to presage the coming of the Messiah. It also incorporates appeals for greater tolerance of the Jewish population. As Jan Piet Filedt Kok put it: “The Jews of the 17th century were obsessed with the coming of the Messiah, which they looked forward to in the expectation that it would put an end to the misery and suffering of the Jewish people. In a time of persecutions in Portugal, Spain and Poland this was not to be wondered at”.

Jacob’s Dream shows the sleeping patriarch, his head resting on a stone, as he dreams of a ladder upon which angels ascend and descend to and from heaven. It was the only one of the four subjects in the illustrations that Rembrandt had treated previously. Menasseh understood the work to be an allegory of the fall of the enemies of Israel, writing in the text that “you will see how three angels descend a staircase … and another who is at the top and ascending, representing the fall of the three preceding monarchies and the escalation in which we experience the last” (quoted in Michael Zell, Reframing Rembrandt: Jews and the Christian image in Seventeenth-Century Amsterdam, Berkeley/Los Angeles/London 2002, p. 74).

The book with Rembrandt’s etchings survives in only five known copies. Other editions exist but these contain often crude engravings after Rembrandt’s original designs, sometimes with significant adjustments to the images. Current scholarship suggests that these are the work of the Jewish artist Salom Italia, who had made an engraved portrait of Menasseh in 1642. Rembrandt’s choice of etching and drypoint for book illustration, although reinforced by engraving, was somewhat unusual since they tend to deteriorate much more rapidly than engraving or woodcut, both of which are thus better suited to producing enough impressions for a book edition. It seems most likely, therefore, that Rembrandt’s etchings were replaced for practical reasons. In the first instance, however, Menasseh did entrust this politically and religiously complex project to Rembrandt, who was neither Jewish nor a professional illustrator. Furthermore, Rembrandt’s illustration of the text “reflects an exceptional degree of cooperation. The alterations Rembrandt agreed to make, even if they involved compromising his aesthetic convictions, attest to an uncharacteristic willingness to revise his work to accommodate Menasseh’s directions … Menasseh, moreover, always under financial pressures, which were particularly acute during this period, could hardly have afforded to pay the fee Rembrandt could command” (ibid., pp. 84f.).

Given that a number of surviving individual impressions, like this one, exist outside the book, and that Rembrandt experimented with some of them on a range of different supports, including vellum and Japanese gampi paper, it seems clear that he used this commission to create highly idiosyncratic prints that could stand on their own. All of these prints, with their rich plate tone and selective wiping, are not accidental trial proofs but were clearly pulled by Rembrandt to satisfy the requirements of a highly sophisticated group of collectors. This is ultimately the reason for their survival, even though they count among the rarest and most sought-after of the master’s prints.